The following is an excerpt from my FREE guide, “A Christian’s Guide to AI.” Click the link to read the full book. Thank you for your support. Please share your thoughts in the comments!

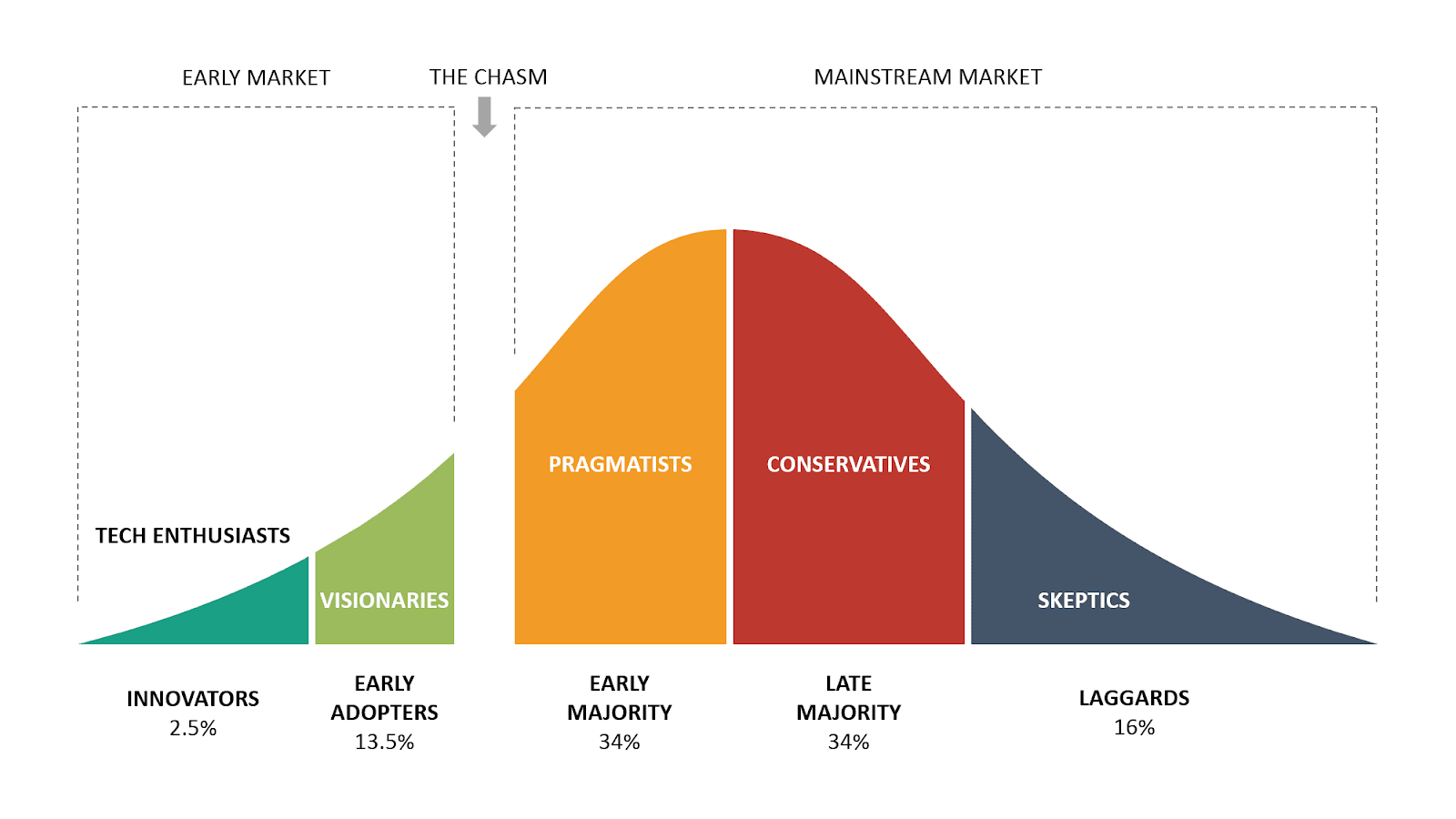

When the iPhone first came out in 2007, did you rush to place an order? If so, you are what sociologist Everett Rogers would’ve called an Early Adopter. In the 1960s, Rogers published a book titled, The Diffusion of Innovations.” In it, he introduced what is now known as the Technology Adoption Curve (though it applies to broader consumer behaviors as well as technology-specific business).

According to the curve, there are five main types of consumers:

- Innovators

- Early Adopters

- Early Majority

- Late Majority

- Lagards

The largest categories, by far, are the Early Majority and the Late Majority at 34 percent of the market, each. What does this mean?

It means that most of us are not inclined to enter the early market. We bide our time, thinking pragmatically and/or conservatively (the laggards are more skeptical) about new technology. The market needs these hesitant thinkers as much as it needs the fanboys and fangirls. The latter (innovators and early adopters) comprise only 16 percent of the market. You wouldn’t know it, though, as sometimes they are the loudest. These folks, whether via passion or commitment bias–shout the praises of technological advances, such as AI. This is important to know because you ought to (A) discern where you are on the spectrum to better understand your response to AI and (B) recognize the echo of the minority as what it is and not a reason to “buy in” without further thought.

Make sense?

With that in mind, it’s time we look at the not-so-pretty parts of AI. You’ll notice that most of these are usage-related. Why? Because we are the ones who create and implement the systems. AI is not inherently good or bad. We, on the other hand, are moral creatures and have value systems.

As the Board Chair of AI and Faith wisely queried, “Can we code morality into AI?” In other words, can a self-driving car make a value judgment between hitting a child in the road or hitting a tree and killing the driver? Whatever “morality” is embedded into AI is rooted in the morality of the creator. Who are we letting make these decisions?

We are responsible for how AI is used and the impact its decisions have. That is to say: We need to be aware of the dangers… and our propensity to flit toward them. We cannot assume that the moral code of AI is biblically informed. Quite simply: this is why Christians need to be in this conversation and why I’m writing this guide.

Environmental Considerations

Sasha Luccioni is in the world of AI, and it’s not uncommon for her to get flak for it. Granted, she is in the field of AI ethics research, but that doesn’t stop strangers from occasionally emailing her with claims that her work will end humanity. “AI isn’t so [popular] right now,” she admits. But AI isn’t going away, and as Sasha shared in a 2023 TED Talk: “We’re building the road as we walk it, and we can collectively decide which direction we want to go.”

One option is to bypass efforts toward sustainability in favor of data. The other is to take a “stop” before diving headfirst into AI consumption. AI doesn’t exist in a vacuum; the choices we make in this nascent stage have massive implications for the planet with which we are entrusted.

As it pertains to said planet, the existence of AI poses two main energy-drainers. Running technology that supports AI uses a lot of power (measured in terawatt-hours, or TWh). Those computers are typically powered by fossil fuels. Burning fossil fuels releases CO2.

As you’ll see, the carbon footprint of training AI is as much of a concern as the actual energy used during functions:

- Training – Machines may be speedy, but they still need to learn to walk like humans. To get a Large Language Model (LLM) like ChatGPT up and running, companies need to input information and repeat simulations; Just like a basketball player taking free throws, LLMs need reps to increase their accuracy. These reps needed to prepare ChatGPT3 used enough energy to power 120 houses for a year. That energy usage is equivalent to driving your car around the Earth one hundred times.

- Inference – “Once models are deployed, inference—the mode where the AI makes predictions about new data and responds to queries—may consume even more energy than training.”

Because AI is more sophisticated than Google, it requires more energy. According to research from the Columbia Climate School, the world’s data centers (which are used to evolve AI processes and operate almost exclusively on fossil fuels) account for more greenhouse gas emissions than the aviation industry. Much of this is stemming from large fans used to keep the technology from overheating, meaning that up to 40 percent of the energy isn’t even going toward the data storage/synthesis; it’s going toward keeping everything cool enough! It is estimated that by 2030, these data centers will use 3-4 percent of power worldwide–that number rises to eight percent in the United States (by 2030).

That’s a lot of science, and if you like that kind of thing, solid: go peruse the resources in the footnotes. For the rest of us: this is sufficient to hopefully drill home the claim that developing and running AI uses a lot of energy, and the rapid uptick in how much energy it uses is concerning. Experts warn that this increase in AI usage will strain the power grid of the U.S. and other large countries. In layman’s terms: We may lose power or find power much more expensive because it’s in limited supply. AI conglomerates do not disclose this energy cost. Few rules are in place, and existing rules have petty pocket-change fines for these tech companies. This is a notable risk.

At the end of the day, we must remember that nothing is free; the cost will likely come back to hurt future generations, particularly if we are reckless now. You and I must consider what ethical AI usage looks like. We must determine how we can use AI in a way that aligns with our individual values. This is something we will discuss in a later section. First, though, we need to acknowledge the ethical implications of AI as a whole.

Ethical Considerations

Last year, I listened to a live presentation on AI in the workplace. The bubbly speaker rattled off a myriad of ways we could use AI, even displaying a bot that looked and sounded human. When it was time for questions, my hand shot up. It was the only hand in the air, but I didn’t let it waver. My question was important.

“How can we prevent this from becoming another classist luxury?” I started. “One where people who can afford to buy into AI services make more money, and those who cannot afford those resources get poorer? What can we do to prevent that?”

To my horror, the presenter glanced around the room as if to say, “Can you believe this girl?” and then answered with a chuckle: “We can’t.”

My brain largely shut down by the time she went on to explain that everything is like that. “AI will be no different,” she shrugged. “That’s just how stuff goes.” Her explanation was not okay with me then, and it’s not okay with me now.

Access for All

When we set something as a standard yet deny access to the majority, it is a serious societal blunder. You should be concerned about this for the same reason you ought to be concerned about equal access in other realms. As AI continues to proliferate in the economic and social landscape, we must have systems in place to subsidize and train those of lower economic standing. Think about it: The people who could most benefit from the help of AI to climb out of poverty, work from home, find a job, etc., are the ones who won’t be able to pay the premiums to access it.

I’m not unrealistic, mind you. I know that data uses energy and energy costs money, and someone must pay the bill. What I am saying is that this bill ought to be considered. I’d be more confident if our nation invested resources to provide free AI training and premium membership to those who need it most. As it is, I am frustrated at the frivolity of AI’s introduction to our world. It goes against my morals to wholeheartedly endorse a system that will further widen the economic gap if current patterns continue.

Representation for All

Let’s imagine a world in which everyone can benefit from the creation of AI. In this world, individuals of all backgrounds and beliefs can access AI. Cool. Beneath access, however, is still the issue of representation. In other words, the tech sector is dominated by males; so the AI systems we use are created by and for men. Lack of representation in the creation of AI tools disempowers minorities. I first realized the extent of this when I read “Invisible Women,” by Caroline Criado Pérez. To my shock, I learned that Microsoft and IBM’s facial recognition is racist from a statistical standpoint–according to an MIT study, “facial-analysis software shows an error rate of 0.8 percent for light-skinned men, 34.7 percent for dark-skinned women.” We can’t take AI at face value–literally or figuratively. The beliefs and data that AI systems are trained on are based on the perceptions of a tiny sample of the general population.

This is nothing new. Search engines have been notorious for reinforcing racism since their release. Then and now: Representation in AI is something to be cognizant of–in terms of development and the product itself. See more in Appendix 3.

Knowledge for Knowledge’s Sake

Humanity’s greatest strength is the ability to feel. It’s a bitter reality to face during hardship, but this capacity also motivates us to explore, think, and connect.

What happens when we take the journey of knowledge away? What happens when we make it so easy to amass resources that we outsource critical thinking in the process? As I’ve mentioned, this is a large concern of mine. We must be cognizant that the money invested in AI is aimed at getting you and me to use it. Lots. Just like social media, AI is not designed for moderate use. It is curated to be attractive and necessary–that’s how the companies make money.

There are various problems with this intoxicating effect, the most concerning being how it incentivizes speed over substance. As we will discuss shortly, that is particularly worrisome for those in creative fields. It highlights the vital question: What is the end goal we have in using AI?

Knowledgeable Reflection

With that in mind, I encourage you to return to the section that tackles the value of critical thinking. Think about the prevalence of AI in your life and find the spot in the sand where you draw the line… It’ll be different for you than for me, but you and I must know where that line is if we ever expect to hold to it.

I use AI to further the creative and process-oriented passions I have. It helps me brainstorm and synthesize data. It also really helps me get organized sometimes. But I decided early on that these functions cannot come at the expense of the creative passions themselves. Why? Because easy is not my goal; authentic art and expression are my goals.

I am a writer; I love writing. So I am writing this paper by myself with no AI assistant to help. That matters a lot to me because it lines up with what I believe about the world and about myself. I like the journey and find value in it. I hope that whatever your endeavors are, you find merit in the process as well.

Educational Considerations

The Dangers of AI section is becoming quite a bit longer than the benefits. That’s not to say that the new technology isn’t worth it–again, that is for you to decide with the help but not coercion of this guide.

This section is longer because fully unpacking the considerations will help you understand the extent to which they matter in your life. There are many benefits; the risks are a little more nuanced and take more time to go through, and nowhere is that more evident than in the realm of education.

Are We Bypassing Critical Thinking?

As the seasoned saints in my life have reminded me over the years, “Back in the day, if students had a question, they’d visit the library to search through an encyclopedia.” Younger me likely rolled my eyes, but age has given me valuable perspective. What a different way of life that must have been!

Furthermore, by that standard, my Google-fied childhood probably seems entitled. I have always been able to research with the click of a finger. Searching a concordance is foreign to me, so I have to think it’s largely unknown by Gen Alpha. This generation of tweens is growing up with next-level research. Forget Google searches, today’s students can utilize AI to help with math problems, final papers, and research. The danger that it poses is clear: It’s easier than ever to take shortcuts in our thinking.

When I was in sixth grade, I did a project on albinism. I perused the library, finagled my way through the Dewey decimal system, and made friends with Ebsco Host. Then I read a few books, supplemented with Google, and wrote my paper. The final product was a crisp essay and display board, both of which were significant to me because I worked hard to create them. To present my project, I first learned how to identify credible information and incorporate it into the greater story I was gathering.

Now pretend I’m in sixth grade again (stick with me for one cringey paragraph of pretend middle school, okay?). If it were 2025, I could very easily complete that project in twenty minutes–I’d plug in website URLs, input a few sources of my writing to teach AI my writing style, add the project requirements, and press ENTER. To finish it off, I’d run the paper through an AI editor and add a few AI images to jazz it up. Project done.

Is AI hurting our ability to reason? This example would suggest that the answer is yes, or at least: it can hurt our ability to reason. To engage in critical thinking, we must be able to come up with novel thoughts that we pump through the cogs of our brain to produce effective conclusions, ideas, or beliefs. When technology gives us the thoughts (i.e., research sources), the machinery (i.e., the AI), and the product (i.e., the paper), the mental load is drastically reduced. Instead of “what direction should I go with this?” we are left with, “which sample of writing do I want to feed the machine to make it more realistic-sounding?”

This isn’t meant to be all doom and gloom, even if my artist heart is biased toward that angle. Just like I never had to rely fully on printed resources, today’s children will never have to rely fully on their own writing or processing. At least not in the way we did in the past.

The effect is that young learners have amassed a wealth of information to learn and experience far more than we could at that age.

They have:

- Amazing tools to increase competency and understanding, like virtual field trips and labs

- The temptation of lazy thinking/living to an extreme that previous generations did not

This is why it is vital to prioritize face-to-face conversation, debate, and learning among our youth; we must encourage reading physical books and talking about information that is spread in public spaces. Why? Because children must learn how to distinguish credible and authoritative voices–amid the billions of other tidbits flying their way–and they must find a voice of their own.

Leave a comment